“We were murdered because we are foreigners”: One year after the Hanau terrorist attack

One year ago today, on the 19th of February 2020, a racially motivated terrorist attack took the lives of nine people and injured a further six in the German city of Hanau, a town east of Frankfurt am Main. The families are demanding Erinnerung, Gerechtigkeit, Aufklärung, Konsequenzen (Recollection, Justice, Reconnaissance, Consequences) for the victims: Ferhat […]

One year ago today, on the 19th of February 2020, a racially motivated terrorist attack took the lives of nine people and injured a further six in the German city of Hanau, a town east of Frankfurt am Main.

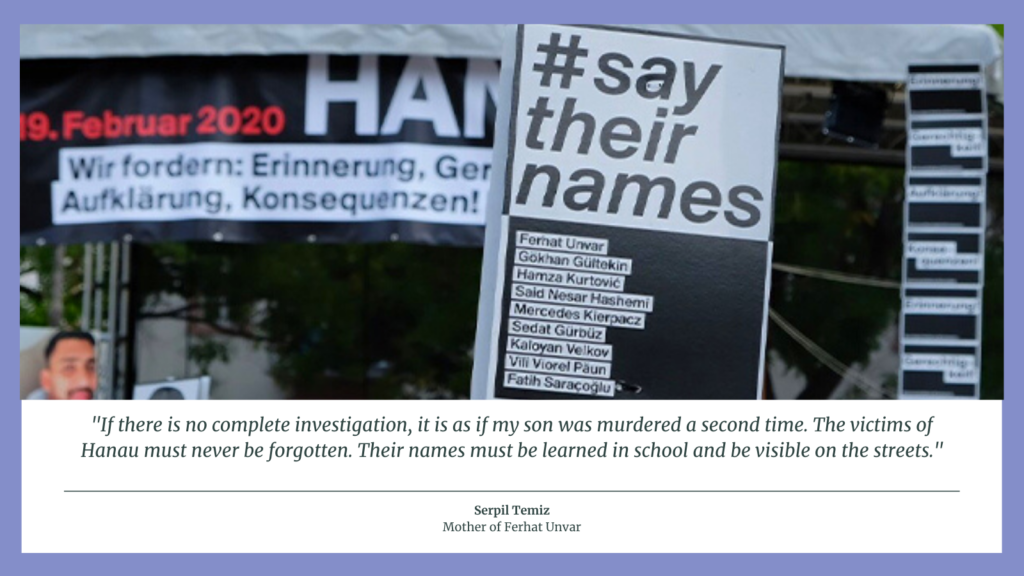

The families are demanding Erinnerung, Gerechtigkeit, Aufklärung, Konsequenzen (Recollection, Justice, Reconnaissance, Consequences) for the victims: Ferhat Unvar, Gökhan Gültekin, Hamza Kurtović, Said Nesar Hashemi, Mercedes Kierpacz, Sedat Gürbüz, Kaloyan Velkov, Vili Viorel Păun, Fatih Saraçoğlu. Posters saying: “We cannot forget, we have to say their names”, started appearing after the terrorist attack in cities across Germany urge. “Hanau was not an isolated case”, one leaflet reads. In the 24-page manifest that the assassin posted on the Internet shortly before his act, he wrote that certain “ethnic groups, races and cultures” were “destructive in every respect” and therefore had to be “completely destroyed”.

As we remember Hanau’s night of terror, Guiti News asks what has been done since to tackle the threat of far-right extremism in Germany within the private and political spheres? We reflect on the horrors that took place that day in Hanau and honour the lives lost.

Guiti News is challenging the conversation surrounding migration. Guiti brings a unique perspective to these narratives: every piece is created in collaboration of European and exiled journalists and artists.

Text: Melis Omalar and Hussein Dirani | Images: Archive of Initiative 19. Februar

The culprit shot three people first at Heumarkt in Hanau, a street-like square that sits about 300 meters from a police station. The close proximity of the station to the crime scene is why the relatives cannot understand where the police were the night of the terrorist attack. Additionally, the police were called several times that night, including four calls from one of the nine victims – Vili Viorel Păun -, to no response.

The lack of an immediate police response allowed the culprit to drive to Kesselstadt, a district in the city of Hanau about two and a half kilometres from the first crime scene. Once there, he killed a further six people. This, the families explain, could have been prevented had the police responded when initially called. After the killings in Kesselstadt, the culprit drove back home. At this point, there was still no sign of the police. At home, the killer fatally shot his mother before killing himself. Five hours later, the police arrived at the flat to find them both dead.

“Recollection”: Many questions remain unanswered

“[The police] let this happen, that these people died”, mourns Mercedez’s father in a Spotify Studio podcast on Hanau. He, as well as others, don’t understand why the culprit was allowed to have a gun licence given that he was mentally ill and had a criminal record. For years, the killer was known to German authorities for paranoid delusions and an extreme far-right attitude. Among other conspiracy theories, the killer was convinced he was being tracked by the German Secret Service.

The families have many questions for Germany that remain unanswered even one year after. Why wasn’t the police responding to the numerous calls the night of the attack? Why didn’t the families know where the bodies of the victims were and what exactly had happened? Why did they have to find out from the news? Why didn’t the families get to say goodbye? Over a week after the attack, and after the autopsy, after their bodies had been cut open, the families finally got to see the bodies of their loved ones. The families had not consented to the autopsy.

“Justice”: Remembering the nine victims

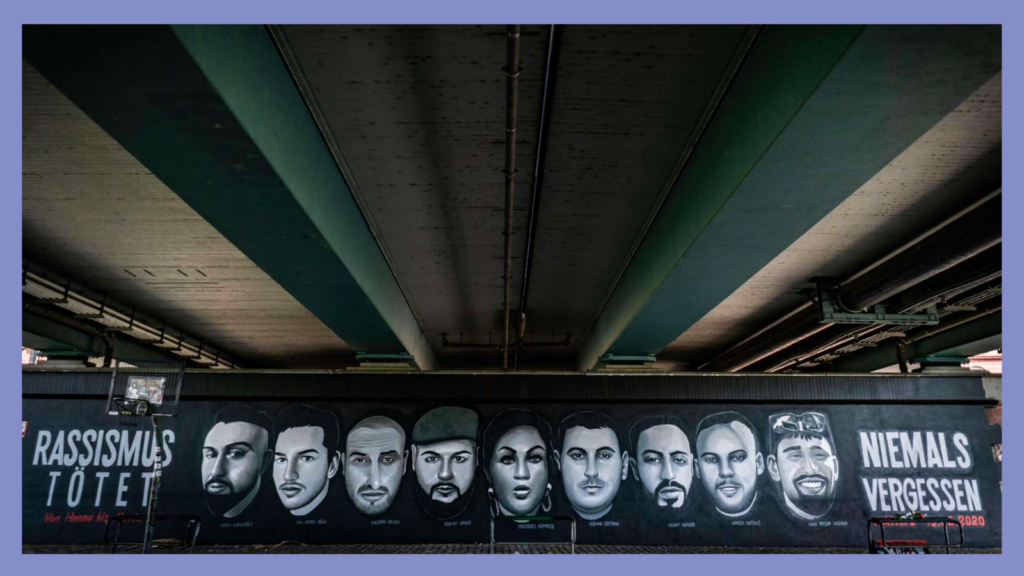

Across Germany today, the families and members of the community have organized memorials, three in Berlin alone, to remember the lives lost and why. Mercedes’ mother, Sophia Kierpacz shares with Der Spiegel: “The Germans always say ‘foreigners, foreigners’, ‘What are the foreigners doing?’. I don’t understand that. Look, our child was killed by a German, a racist.” In the following, we portray the people murdered that day in Hanau.

Ferhat Unvar

Ferhat (23) wrote poetry and wanted to write a book. “We are only dead when we are forgotten”, one line reads. He was born in Germany to a Kurdish family. He was a heating and gas installer and wanted to start his own company. Ferhat often met with friends in the Arena Bar, where he was shot. His mother, Serpil Temiz Unvar, founded an education initiative in his name. She wants to know why some claim that the ’victims weren’t foreigners. “Of course we were foreigners. That is exactly why we were murdered. Structural racism killed us. Nobody takes that seriously.”

Hamza Kurtović

Hamza (22) was his own biggest critic. “He always gave 100%, anything else was out of the question for him,” his father Armin Kurtobic remembers of him. Hamza was born in Germany just like his father and three siblings. The family originally came to Hanau from Prijedor in Bosnia-Herzegovina. He had just finished his apprenticeship and lived close to the perpetrator. Hamza was shot in the Arena Bar while waiting for his friends. In the police report, he is falsely described as Mediterranean-looking (südländisch). Hamza had blue eyes and blonde hair.

Said Nesar Hashemi

Said Nesar (21) was a trained machine and system operator. He was German-Afghan and grew up in Hanau. He wanted to complete his further training as a technician. Said loved the summer and travelling. His sister says of him: “He was always there for people who needed his help.” Said, Hamza, and Ferhat are buried next to each other. The three grew up together and were close friends.

Vili Viorel Păun

Vili (23) spoke six languages. He was a Roma from Romania and the only child of his parents. He came to Germany at the age of 16 and tried to stop the culprit the night of the 19th. Vili saw what was happening at the first crime scene, where the culprit tried to shoot him. He began calling the police numerous times unsuccessfully, but no one came to help. So Vili followed the culprit in his car, trying to stop him, up until a Lidl parking spot where the culprit shot Vili in his car. There now stands a memorial in his name.

Mercedes Kierpacz

Mercedez (35) was a best friend to her two children. She was German-Romani with Polish roots and was born in Offenbach. “We are Roma”, her father emphasized to the press and police, “and we are very, very few.” Mercedez worked at the Arena Bar the night of the 19th of February. She leaves behind a son (17) and daughter (3).

Kaloyan Velkov

Kaloyan (33) had only lived in Germany for about two years. He was the landlord of the Bar La Vorte next to the Shisha Bar Midnight and wanted to support his family in Bulgaria financially through his work. Kaloyan’s family, who is in Bulgaria, no longer want anything to do with Germany. His father didn’t accept the 30,000 euros that the victims’ parents received. He did not want to. Kaloyan leaves behind a son (7).

Fatih Saraçoğlu

Fatih (34) hadn’t lived long in Hanau. He came to Germany to become self-employed as a pest controller. His brother, Hayrettin Saraçoğlu, describes him as “friendly and hard-working. One always felt safe and secure around him.” When his mother died a few years ago, Fatih was there for his father and cared for his family.

Sedat Gürbüz

Sedat (29) was the owner of the Shisha bar Midnight, the first scene of the terrorist attack. He lived with his parents in Dietzenbach, a city 12 km southeast of Frankfurt am Main, where he grew up and played football for the local club for many years. A good friend calls him a “beloved brother. He was always laughing and couldn’t hurt a fly.” He leaves behind a brother.

Gökhan Gültekin

Gökhan (37) was born in Hanau. His Kurdish parents came from Ağrı, Eastern Anatolian region of Turkey, and had lived in Hanau since 1968. He was a trained bricklayer and worked as a waiter part-time. For Gökhan, his family was most important. He cared for his father, who had cancer, and supported his mother. His father passed away a few weeks after Gökhan was murdered.

“Reconnaissance”: The political response

Many high-ranking officials and politicians attended the funerals of the nine victims, among them German Chancellor Angela Merkel. UN-General secretary António Guterres expressed his condolences to the families of the victims and called for an intensified fight against racism, anti-Semitism and hatred of Muslims. Similar comments were made by French President Emmanuel Macron.

The families, however, remain skeptical about how willing authorities and officials are to put these words into action. Hamza’s father, Armin Kurtović, “doesn’t trust the German authorities” anymore. Ҫetin Gültekin (46), Gökhan’s brother, shares similar frustrations with Die Zeit: ”According to the German federal government, 1,200 right-wing extremists have more weapons than they did in February 2020. These policies frighten us. Should conditions as in America be created here? And do you believe that someone like me, someone with a Turkish passport, would be allowed to have a weapon? It scares me where Germany is headed.”

“Consequences”: Creating an anti-racist climate

Because the killer is dead, there will be no legal process. On the anniversary of the attack the chairman of the association DeutschPlus, Farhad Dilmaghani, as a representative of organizations focused on migration, demands in Der Spiegel: In order to prevent further attacks as Hanau, Germany needs “an anti-racist climate in our society: more knowledge and education about racism. Structural changes in the permeability of our country and new instruments such as a Ministry for Social Cohesion, Anti-Discrimination and Migration or a Federal Anti-Discrimination Act.”

But so far, nothing has been implemented on a political or policy level. To counter the inaction, the families started their own outlets. Together they created Initiative 19. Februar Hanau which advocates for social and political change, aims to tackle racism in public and political spheres in Germany, and wants to ensure that attacks like Hanau never happen again. The initiative also offers a physical space in Hanau for the families and members of the migrant community to come together and find “solidarity, rather than separation.”

Even one year after the attacks, the families are left with many questions unanswered and concerns ignored. In particular, the families have repeatedly voiced their concern about the father of the culprit. “He is a ticking time bomb”, the father of Mercedez expresses his distress. The relatives of the nine victims also see a serious threat in the assassin’s father. And they don’t want to wait for legal authorities to investigate the 73-year-old pensioner. They have now filed a 16-page police report against the father. There is an initial suspicion, the document states, that the father knew about the planned acts and even encouraged his son to pursue them.

But the families haven’t given up. Serpil Temiz Unvar, the mother of Ferhat, wants to see a Germany where no mother ever again has to tell her children: “You have to work twice as hard as the German kids.” With the education initiative, Serpil wants to combat racist structures and systems in schools, and offer instead a diverse range of engagement and education in Germany. “If my son saw what I am doing now”, Serpil Unvar shares with Der Spiegel, “he would say: Mama, are you mad? Do you think you can change anything in this country?”

Every week we share stories from around the world in English. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, and Instagram to stay connected.

Support our work and independent journalism with a donation to Guiti News.