Decolonizing our countries and curriculums

Since the killing of George Floyd, Breonna Tyler, Jacob Black in the US at the hand of police violence, among over 100 other people of color this year alone, protests and greater movements have grown across cities and countries. Black Lives Matter dominates with its clear message: it is time for the lives of Black […]

Since the killing of George Floyd, Breonna Tyler, Jacob Black in the US at the hand of police violence, among over 100 other people of color this year alone, protests and greater movements have grown across cities and countries. Black Lives Matter dominates with its clear message: it is time for the lives of Black people to finally be respected and for police violence to be considered as an issue that needs to be dealt with properly and urgently. These claims do not come from anywhere but are directly linked to the colonial history of the countries where the protests are taking place. To face up to this issue, it seems necessary to start re-educating ourselves in one of the most symbolic places of all: schools.

Guiti News is challenging the conversation surrounding migration. Guiti brings a unique perspective to these narratives: every piece is created in collaboration of European and exiled journalists and artists.

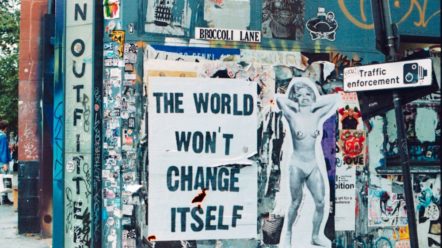

Text: Cécile Massin and Melis Omalar | Picture: Cécile Massin and Fill in the Blank UK

Colonization in school curriculums: The UK and France face their past

In the UK and France, and across the world, institutions and individuals have increasingly become involved with Black Lives Matter – the movement that is aiming to awake change beyond the current moment. Among other goals, Black Lives Matter brings awareness to the disparity that largely links to the education system where these hegemonic perceptions are taught and perpetuated. Following the repeated unjust killings of Black people in the United States, the protests have shed light on structures of systemic racism across the globe. In cities across the UK, such as Bristol and London, protesters took to the street over the last months.

Among them, Antonia (18) from Fill in the Blanks. The activist group led by students from former British colonies is seeking to mandate the teaching of colonial history. “It is critical that we think about how Great Britain achieved its status in history,” Antonia points out. With the lack of action in politics or policy, protesters took it upon themselves to confront and challenge the history of the British Empire. This began with the toppling of the Edward Colston figure three months ago in Bristol and since then, Sadiq Khan, the Mayor of London, ordered a review of the statues, street names, the names of public buildings of the city to make sure they reflect the capital’s community and commitment to removing those with links to slavery.

“Statues are not used to teach history,” Antonia emphasizes. “Rather, they cement and illustrate history. They represent who we are proud of.” But rethinking public representatives is just the first step in confronting the country’s colonial history…

A particular version of history

There are almost no countries in the world where talking about the colonial past is easy nor where teaching it is possible without being more or less influenced by the ideologies that permeate our society. As such, France and the UK are not an exception and ways of addressing the issue of colonization within history curriculum’s has changed a lot over the years, explains French historian Laurence the Cock.

“My ancestors were enslaved and I am being told to be proud of it”, shares Antonia. The lack of colonial education is found throughout history books in Europe. In the United Kingdom, “British values” that include democracy and liberty, are part of the school curriculum. The same one that denies violating those exact rights of Black people and minority groups. To a large extent, schools do not teach the horrors and realities of the ‘Great British Empire’. Educational organisations like Fill in the Blank are concerned with a government that only portrays “a particular version of history.”

From the beginning of the 20th century to the Second World War, colonization was presented as a moral duty in school teaching. France and the UK were portrayed as heroes helping other nations which were seen as inferior. But after the war and the immense traumas that it left behind, a big change happened in people’s mentality. This had important consequences for the history curricula. After all the horrors that happened during the war, how could it have been possible to keep on teaching history, and more specifically colonization, to the students in the same way as it used to be before? But it was only in the 80s that the biggest change took place: as a part of the French population turned to the far right, the teaching of colonization and slavery within the history curricula became a political topic on its own. Nowadays, the teaching of the French colonial history to the students is directly immersed within the public debates and several legislative proposals have been made during the past decades to address this issue. If, in 2001, the “Loi Taubira” recognizing slave trade and slavery as a crime against humanity, in 2004, the article 4 of the “Loi Mekachera” was proposed to teach the “positive role of the French presence outside of the hexagon and in North Africa” to French students. This proposal has been abandoned due to all the negative reactions that it generated. However, the sharp debate that emerged in reaction demonstrates that, in France, the teaching of the colonial history has gradually become part of the political debates, testifying to the different visions that one wishes to teach to the future generation.

The shortcomings of current school programs

After a several important changes, the current French school curricula now deals with issues of colonization and slavery. For instance, in the fourth grade of college, the first part of the history program highlights the issue of the ‘slave trade in the 18th century’ as well as the ‘plantation economy in the colonies’, while the second one deals with ‘the colonial conquests and the colonial societies’. A few years later, in high school, the students are taught ‘the constitution of colonial empires’ as well as ‘the slavery before and after the conquest of the Americas’ while a year after, the third topic of the history program tackles, among others, the ‘colonial policy of the Third Republic’ and the reasons why it was founded. In the final year of high school, the second theme invites students to consider “how post-war France ceased to be a colonial power and regained an international role”.

In the United Kingdom however, students learn little about Britain’s colonial past. This is why student and staff countries have been petitioning for decolonization to be put on the National Curriculum and systematically ensure its teaching in all schools across the country. “Many of us left school confused, not understanding the history of our own ancestors and were denied fully understanding our own identities,” write former Park High School students from London. Pupils and parents want to make sure that compulsory education no longer produces generations oblivious to the complex and violent realities which constructed the nation’s history. “The British Curriculum dedicates plenty of attention to the violence of others, but will not teach you anything about the brutality of British colonization,” the students shared in an open letter to the school.

“Black lives are not seen as equal in the UK”

Are these programs, as they are currently taught, satisfactory? Do they meet the expectations of the young generations they are addressed? What do they tell us about the current relationship to our colonial histories? These are the questions that we asked Baptiste, a history teacher in an Île-de-France high school, who sees major gaps and pitfalls in the current French history curriculum.

For Baptiste, there is, above all, a fundamental problem within the history curriculum: the impossibility to address what colonization has been as a “system”. “The issue of oppression, of what the system itself has been, is never really asked. We stick to the analysis of specific historical events without trying to understand and explain what actually binds them”. Yet, how could one try to analyze these events without asking itself what is the underlying structural logic? In the same way, how could we tell the students the history of colonization without telling them the story of the ones who’ve been colonized? The point of view of the former colonists, of the metropolis on its former colonies, remains largely predominant while the point of view of the colonized people counts among the great absence of school programs. The way the historical facts are told is therefore largely unilateral and does not enable one to take the measure of the upheavals induced by colonization for the colonized populations themselves. What is the history taught by the teachers to the new generations coming from former colonies? For Baptiste, the history programs as they are currently constructed do not meet the expectations of the students, and even less of the ones from migrant backgrounds. “The history of these pupils, of their parents… this is a subject that we never address. Thus, these students have the impression that they are not concerned by the history that we are supposed to teach them, that they are perpetually left out”. This pitfall within the current history program, Baptiste chose to tackle with his students rather than to ignore it: by quoting the rapper Kalash Criminal. Kalash was born in Zaire and declares in one of his hit songs: “My history teacher did not know Thomas Sankara, I find it regrettable…”

Young activists and filmmaker Jemmar Samuels similarly learned little about colonial history in school “I had to go out and teach myself”, the 23-year old shares who used resources like Brixton Black Women’s group and the Black cultural archives to educate herself. As a Black & Ethnic Minorities Officer at Brunel University London, Jemmar became a source for others to hear and learn from. “But now, these things are gonna be more accessible, more widely available.” Yet, she is worried how likely it is for schools to be teaching students about systematic racism when it is part of that exact system: “What scares me the most is not that the police are killing us, but that people are justifying it.”

Without changes in education and politics, activists like Jemmar and Antonia do not see these ideologies and injustices disappear. “Black lives are not seen as equal in the UK”, Antonia reminds. “You can distance yourself from the reality of history and be blindly proud of it.”

Towards new stories?

Very often, there is a significant gap between the content of the school curriculum and the debates which agitate our societies. When will the point of view of the former colonized and other oppressed groups be taken into account in school curricula? When will there be a place in school programs for young generations coming from former colonies? Who are all trying, somehow, to find their place in this particular version of history that they are taught? These questions remain unanswered today but, for the past thirty years, different movements have been developing to rethink the way we teach history. Rather than from a Eurocentric point of view but by including the “Other’s” point of view, namely one of the formerly colonized peoples. Contrary to what the French President claims, it is far less a question of erasing any “trace or name of its history” but it is about reconsidering and teaching history by finally taking into account the realities and varying perspectives that reflect the colonial past..

On the contrary are the reactions of politicians and public officials in the United Kingdom: Prime Minister Boris Johnson said that the removal of statues and street names “would be to lie about our history, and impoverish the education of generations to come.” These statements were met with public push-back and were followed later by announcements of a cross-party group of 30 politicians asking for a re-evaluation of the school syllabus. “If there was a change in education”, Antonia says, “I would be hopeful for a better future.” Until that is the case, the young activist group will continue challenging and campaigning for a country and classroom where black history is taught as history.

Every week we share stories from around the world in English. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, and Instagram to stay connected.

Support our work and independent journalism with a donation to Guiti News.