Lebanese voices | 3

On August 4th, 2020, two tremendous, devastating explosions shook Beirut. These caused the death of at least 200 people, injured more than 5,000 people, and left another 300,000 homeless. In our series Lebanese Voices, we are giving a voice to those who have witnessed the destruction. Guiti News calls attention to not only this disaster […]

On August 4th, 2020, two tremendous, devastating explosions shook Beirut. These caused the death of at least 200 people, injured more than 5,000 people, and left another 300,000 homeless. In our series Lebanese Voices, we are giving a voice to those who have witnessed the destruction. Guiti News calls attention to not only this disaster but also to the political situation in Lebanon, their desires, and hopes for the future.

Guiti News is challenging the conversation surrounding migration. Guiti brings a unique perspective to these narratives: every piece is created in collaboration of European and exiled journalists and artists.

Text: Cécile Massin and Hussein Dirani| Picture: João Sousa

When I ask Zouzou to introduce herself, she answers maliciously that no one needed to know her real name. “People call me Zouzou. It is fine like this,” she says. “I am a 25 years old Syrian girl. I came to Lebanon about four years ago. My life in this country has been really tough in many ways, and I want people to know it. But I do not think that anyone could understand it without going back to the roots of the relations between Lebanon and Syria”.

Lebanon and Syria – two brothers?

Since the beginning of the Syrian Civil War in 2011, Lebanon is the country that has hosted the largest number of refugees per capita. Among them are around 1.5 million Syrian refugees, according to the UNHCR. This situation has created a great deal of tension within the Land of Cedars between Syrians and Lebanese. As Zouzou highlights, it is impossible to understand the current situation for most Syrian migrants and refugees in Lebanon without going back to the roots of the relationship between Syria and Lebanon.

“When I first arrived in Lebanon”, explains Zouzou, “I realized that I didn’t know anything about the real story between our two countries. In Syria, people have been brainwashed by successive governments. For example, as a Syrian child, you are taught over and over again that the Syrian Army went to Lebanon to ‘end the civil war’ and protect what they used to call our Lebanese brothers and sisters. But no one ever tells you the real reason. No one tells you why the Syrian troops were sent to Lebanon. If you ever dare to talk about all the violence, the crimes, the killings committed by the Syrian Army over there, you know that you might end up being tortured and accused of treason.” The silence surrounding the relationship between these two countries is, until now, very hard to tolerate for a lot of Syrian and Lebanese citizens. In Syria, talking about the role played by the Syrian Army during the Lebanese civil war remains a big taboo. That is also the case in Lebanon, where political parties still try to instrumentalize the historical past between the two countries for their advantage. It is in this very tense context that Zouzou arrived in Lebanon in October of 2016.

“As a Syrian citizen in Lebanon, you have to fight all the time“

When Zouzou arrived in Lebanon, she realized very quickly that she would never be treated the same way as a Lebanese citizen. “When I got there, I stayed for a few days in the South of Lebanon, and then I moved to Beirut. I got a job and a shared apartment, everything was going well for two or three months. Then I got fired from my first job along with other Syrians and it all started to get ugly,” Zouzou begins to explain. “The employers had promised us that they would take care of the legal papers. But they did not and they just fired us,” she added.

Like many Syrians in Lebanon, Zouzou is living and working illegally in the country, which puts her in a very precarious situation. Whatever job she found, “the same thing kept on happening,” she explains. “Employers would tell me that they would do my papers, but they never did so. I just gave up on it,” she adds. “There was just one time, I tried to take care of the papers myself. A guy was supposed to help me, I gave him all my savings which were around 1200 dollars. He was supposed to help me get legal documents with all this money, but he just left with everything. He basically disappeared.” Since then, Zouzou has not been counting on anyone except herself to take care of her administrative situation.

In Lebanon, her employers not only gave up on helping her regularize her legal situation but also took advantage of her precarity to mistreat her. “In the restaurant, I was working in, I was not even allowed to speak Arabic with the customers. This was because of my accent. For my employers, my accent was too heavy and kind of weird for the Lebanese ear… So I had to speak English all the time,” Zouzou explains. “The owner would not also let me wear my cross around my neck because he was saying that in this restaurant, no religious signs were allowed… But the minute you walked into the restaurant, the first thing that you could notice over your head was an enormous cross and right next to it, a photo of Saint Charbel, a famous Marone monk, and a priest from Lebanon…” These are events that one could consider as simple symbolic details but which complicated Zouzou’s start in Lebanon.

Working without any legal documents in Lebanon also had practical consequences for Zouzou. “After a while, I started working in a restaurant in Mount Lebanon Governorate. We were not making a lot of money there because it was our first year of implantation and there was a lot of competition between restaurants. Our employer refused to sign a contract with any of us, and as a Syrian, I could not say anything. He blamed on us the fact that we were not making enough money, and even if we had agreed on my salary, he did not pay me anything for the first two months and refused to give me any days off,” explains Zouzou. “Not only did he not pay me my salary, but he also owes me money because I was paying a lot of things for the bar from my own savings. There was nothing I could do because I had no contract. But actually, in Lebanon, even if I had a contract, I could not have done anything cause I do not have any legal papers.”

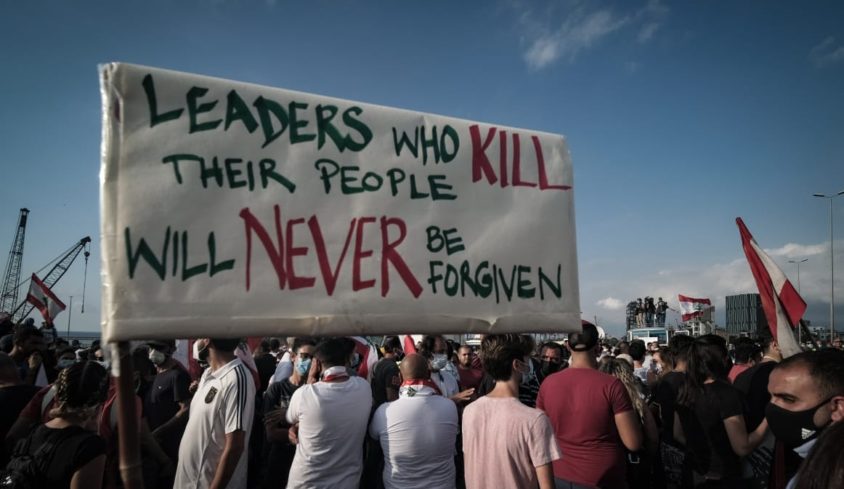

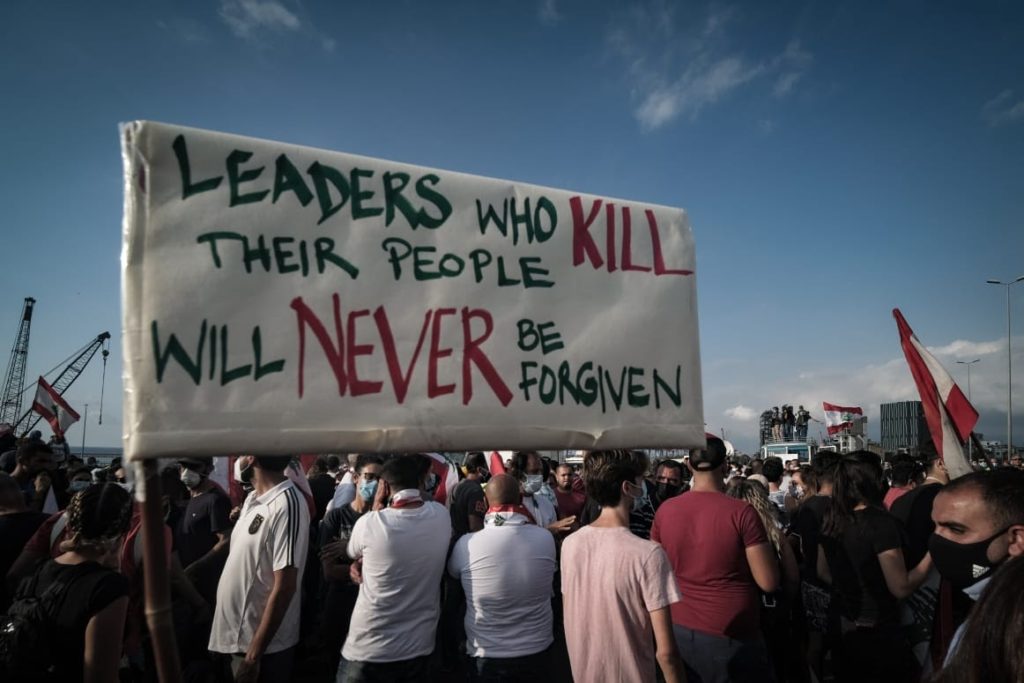

It has almost been two months since the blast, six months since lockdown restrictions were announced in Lebanon, and a year since the revolution started. The least one could say is that the Land of Cedars has been experiencing an enormous amount of traumatic events this past year. In regards to these events, the Lebanese government happens to be entirely unable to listen to the claims and concerns of the population. It also has failed to protect it from the dangers it has had to face. Worse still, the government and militias have tried to frighten their own people, preventing them from claiming their basic human rights.

A Syrian and a woman in Lebanon, a double penalty?

As a woman in Lebanon, Zouzou is being denied her fundamental rights. This includes being paid for the work she was doing. Even more so, she was persecuted, suffering from sexism and sexual harassment.

“I remember going once to an interview in Sin El Fil, an east south suburb of Beirut. It is one of the firsts sexual harassment experiences that I can recall in Lebanon. I do not want to talk about what happened within the office… I can just say that it happened, and I left,” Zouzou recalls. “I was really shocked and traumatized by the interview. I finally got a taxi, and when I almost got home, I remember that the taxi driver got out of the car and said ‘excuse me a few minutes, I need to pee’. I thought ‘okay, there is nothing weird with that’. But when I looked at him, he was standing right next to the window, his penis out, asking me very calmly if I had napkins… I was unable to react. All I could do was throw his keys away to make sure he would not follow me and run away as fast as I could,” she remembers. “I cannot even tell you how many times I have been in a cab, and the driver started touching himself or in a bus, and the person sitting next to me started doing the same thing… It is… pretty basic… kind of ‘normal’ around here. I do not know the right word, but you get it.”

Women in Lebanon: in search for justice

“So many things happened to me. I could not tell you them all. One of the most recent ones was when I was working in a bar in Mar Mikhael. One night, the owner told me to go with him to the room where all the employees go if they want to discuss something privately because he was sad that day. This room is the place where we keep the money, the equipment for the restaurant, and everything, so I did not expect something weird to happen. So, we went to that room, he locked the door, and when I turned around, he was unbuckling his pants. What the fuck! He said that I was his friend and that I had said that I would do anything not to make him sad! I immediately unlocked the door and went out. But after that, he started hating me and treated me horribly.”

When Zouzou finally left that place, she found another job after a while in another restaurant in Gemmayze, a popular area in the Christian neighborhood of Beirut. “Every time someone would be racist towards me, I would go to my manager to ask him for support, but he was only saying ‘this kind of thing happens all the time, just deal with it. What are we going to do? Erase the whole history of the Syrian Army in Lebanon? No, so get over it.’ What the fuck… I was not even born when that happened… Why am I getting persecuted for this?”, wonders Zouzou. “That was challenging. But I was dealing with it. In the end, I got used to not complaining. But the sexual harassment experience that I have had there led me to leave the restaurant. It was rock bottom…” she confesses. “The guy who harassed me was a supporter of Hezbollah, a powerful Shia political party and militia here in Lebanon. I knew his religion. In Lebanon, we all know each other’s religion, but I had not even considered the fact he could be powerful or that he might have connections… I went to my manager, and I told him what happened, but, as usual, he just said that ‘the police station is right next to us, go file a complaint’. But you can not even file a complaint because they would deport you, you have no legal documentation! ‘Forget it’, he said, ‘I can not do anything because he is one of the Hezbollah people’. But I could not work with him anymore. I was having nightmares because of that place.”

Since this traumatic event, Zouzou has been out of work. In Lebanon, it is still incredibly hard for people to have their rights accepted, especially when you are a foreigner and a woman. Zouzou was in this very complicated situation since the thawra began in October 2019…

Participating in the thawra as a Syrian: between shared goals and the fear of being arrested

When the demonstrations began in October, Zouzou went down the streets with her Lebanese friends to support them. “In the beginning, it was pretty peaceful. Many people were singing and dancing. It was not much of a thawra back then. I went to a few protests, we were having fun,” she remembers. “I was supporting the people demonstrating. I know that Lebanese people are tired of this shit. I have been saying it for years! ‘Why the fuck do you follow these leaders? They are just dividing you and robbing you whenever they are okay with each other and make you kill each other whenever they are not’. So I went down the streets to protest”, she adds.

Zouzou’s friend’s claims are clear: “My friends, they want all politicians gone, literally all of them. That is the whole point of it. There is something they always tell the political leaders in Lebanon: ‘whenever you fight each other, you kill us. And when you makeup and become friends, you rob us’. In Arabic, it sounds more on target, but that is pretty much the best translation I can think of. This sentence summarizes everything that needs to be said. There is nothing good that could ever come out of them, ever. And it would be stupid and ignorant to think that they would ever do something good for this country, any of them”.

Zouzou shares her Lebanese friend’s opinion about the current government and immediately went down the streets with them. But as a Syrian, it started to become dangerous to protest. “Progressively, we started hearing rumors that Syrians were getting arrested during the demonstrations. It got really dangerous for me to go, and my girlfriend would not let me, so I thought I could support in other ways. I was following what was happening mainly online and through my friends.”

Lebanon has been turned upside down by the blast

When the explosion happened on August 4th, everything changed. Zouzou, who, until then, had decided not to go down the streets and demonstrate, to preserve her own safety, decided to join the Lebanese population. “I went down the streets two or three days after the explosion. It was huge. If I am not mistaken, it was the biggest demonstration ever since October 17th. I was so happy. Everyone was there. I was thinking: ‘Khalass, we are done. Fuck it. Fine, I am Syrian, I will get arrested, fuck it. After this explosion, it was like… I do not know… It was rage. Khalass, I do not give a fuck anymore, I am going down.’ So, I went down to protest.”

The rage Zouzou felt after the explosion, is shared by many people in Lebanon. To such an extent that people, who had been affiliated to a specific Lebanese political party, changed their opinion. “Everyone was demonstrating”, Zouzou emphasizes. “Everyone was there, even my friends who were still hung up on their political parties just turned on them and went down the streets to protest. My girlfriend’s family as well. Even her grandma, who had been supporting Michael Aoun her whole life… Even she was like: ‘Fuck them, fuck them all, Khalass, we are done’. It was unbelievable”.

To Zouzou, the anger was as immense as the trauma caused by the explosion. “When the explosion happened, I was in Beirut. But I was not hurt because I was in Ain El Remmaneh, which is not in the area directly touched by the blast. My girlfriend, however, was in Gemmayze. We did not know what was happening. We could not access any information. I thought that maybe it was war, or an attack from Israel, or something related to Hezbollah… When I could finally call my girlfriend, I asked her if she was okay. She was repeating: ‘I don’t know’. I repeated, ‘Are you okay? Look at your body, check yourself, are you hurt, are you okay?’

But she was still saying: ‘I do not know.’ She was shaking and terrified. I told her to go back to the place where she was working because I remember that they had a basement there where she could hide. But when she went back there, they were all hurt. All the staff and all customers were bleeding… She finally took a taxi, and I met her more than an hour later because the streets were destroyed badly,” Zouzou explains. “In a way, my girlfriend and I both got really lucky because we are both physically okay. But my girlfriend is still having nightmares. On my side, I am still very anxious and depressed. I am smoking and drinking coffee all the time…” she says. “I am becoming an angry person, angry at everything and everyone, for every little detail. When French President Macron came to Lebanon, they were making some form of show in the sky with a military helicopter or something, drawing the Lebanese flag in the sky… You are too close to the buildings, man! We thought that another explosion could happen any minute…”

Almost two months after the blast happened, the memories of the explosion have not disappeared from Zouzou’s mind. And yet, she tries stay hopeful and to continue believing in a better future. But her situation remains very precarious in Lebanon.

“I’m blessed to have received help from LGBTIQ+ community, the government has not done anything at all…”

When the explosion happened, Zouzou had been homeless for almost two months. “I used to live with my girlfriend until her dad, who is a supporter and member of Michel Aoun’s party, the Free Patriotic Movement, found out about us. They kicked me out of the apartment, saying that he would deport me if I ever went near his daughter again,” explains Zouzou. “That is the worst thing that ever happened to me in Lebanon. I was homeless, poor, with no job and forced to stay away from the love of my life,” she adds.

After the explosion, Zouzou, like many other Lebanese and Syrians, deplores the complete inaction of the Lebanese government. “Everyone was helping except the government. They did not do shit! And they kept on lying. For example, the funny thing with Hezbollah is that two or three days after the explosion, Hassan Nasrallah went on TV after complete silence on his side and said: “We had nothing to do with it, we had no idea about anything that was in the port of Beirut. We know about the Haifa port, the one that is in Palestine, more than we knew about the port of Beirut”. But every single person in Lebanon knows that Hezbollah knows everything about everyone regarding every matter in this country… If you really follow them, their lies are incredibly pathetic and stupid.”

Despite the inability of the Lebanese government to take care of its own people after the blast, Zouzou and her girlfriend have had the chance to crossroads with persons who took the matter into their own hands and helped them a lot. “Two people changed my life since the explosion happened,” Zouzou shares. “There is Sandra Melhem, the owner of Projekt Ego night club, and Dayna Ash, the manager and founder of Haven for Artists NGO,” she specifies. “Since the blast, Haven for Artists has been turned into a shelter for many vulnerable people. Among them are lesbian, transsexuals, and migrants. I stayed there with two migrant workers, a transsexual woman, and her Palestinian boyfriend. They gave me cash, food, clothes, and they got a nurse to check on me, and my girlfriend. They even hooked me up with a great therapist to take care of my mental health. They told me to look for a proper apartment, no matter the rent, just anything where I would feel comfortable and safe. So, I found a place. They are going to pay its rent for as long as they can from the donations they have received…”

Solidarity within the LGBTIQ+ community is what saved Zouzou after everything that happened to her these past few months. “I am incredibly lucky to have found Sandra and Dayna. They really do an amazing job for the LGBTIQ+ community but also for the domestic workers who have been trying to go back to their countries since the beginning of the crisis. To me, Sandra is the mother of the LGBTIQ+ community in Lebanon. As a member of that community, she has proven more than once that she is there. She is always there for every single one of us. These are people like her and Dayna and their teams who are the ones that are making an actual change, a positive change in people’s lives,” says Zouzou.

“I just wish someone could finally hear us out”

Now, Zouzou and her girlfriend are trying to leave Lebanon. A few weeks ago, Zouzou created a GoFundMe to gather some money, but until now, it has not been working as she had expected. The Canadian Embassy does not answer any of her calls or emails. So, Zouzou has been thinking of camping in front of the Embassy. Just as migrant workers have been doing for weeks. “When you google the telephone numbers of Embassies in Lebanon right now and try to give them a call, you will get an answering machine telling you that you can only call them if you are a citizen of this or that country. If you have any other business, there is no option for you. And if you email them, or if you try to reach them on their official website, you will only get an automatic reply that says bullshit, and they never get back to you. So these are my options right now: either the GoFundMe works out, or I will literally camp in front of the Canadian Embassy until someone finally hears me out.”

Every week we share stories from around the world in English. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, and Instagram to stay connected.

Support our work and independent journalism with a donation to Guiti News.