Finding ‘Home’ Through Creative Art Therapy

What is home? Can forcibly displaced people ever feel at home in an alien country? Often, the sense of feeling at home is taken for granted. But, feeling homeless in a country that you do not feel is yours, despite having a physical place of residence, can have unsettling and destabilising effects. We are joined […]

What is home? Can forcibly displaced people ever feel at home in an alien country? Often, the sense of feeling at home is taken for granted. But, feeling homeless in a country that you do not feel is yours, despite having a physical place of residence, can have unsettling and destabilising effects. We are joined by Elias Matar, Palestinian performer, director, theatre practitioner, drama therapist and youth well-being coordinator to explore how the unconventional means of art therapy can help refugees and migrants get closer to the feeling of home once again.

Guiti News is challenging the conversation surrounding migration. Guiti brings a unique perspective to these narratives : every piece is created in collaboration of European and exiled journalists and artists.

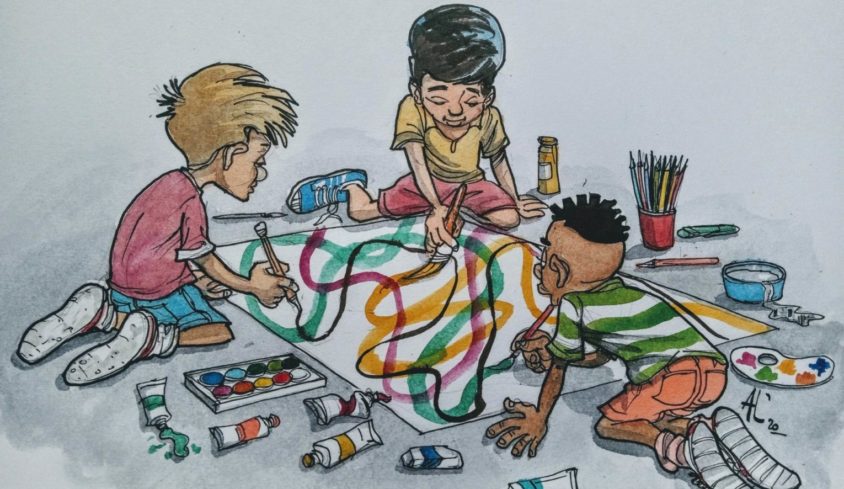

Text: Mana Shamshiri and Somar Bakir / Drawing: Al’Mata / Photographer: Dia Batal

Elias is a self-described paradox: a Palestinian with an Israeli ID. He currently works as a youth well-being coordinator at Barnet Refugee Service with young unaccompanied minors who have newly moved to the UK. He holds an MA in Movement and Drama Therapy from The Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, London and is the founder of the El-Bayet Centre for Performing Arts & Drama Therapy.

Guiti News: Tell us a little about your work and the El-Bayet Centre.

El-Bayet means ‘home’ in Arabic. It’s a community centre that works with the Arab community and diaspora living in London. We use art and performing arts to explore the themes of communication and integration, to teach Arabic and to hear people’s stories. I offered very basic things in the beginning: fun activities, storytelling, drama workshops and then started to offer talks about how to support people from Middle Eastern and Eastern backgrounds in art therapy. I have collaborated with the Arab British Centre, The Mosaic Rooms and The Institute of Ismaili Studies. We facilitated some ERASMUS+ sessions and did some work with the British Council. The main aim was to meet this community in London and try to expose it to art as a methodology, a tool to explore difficult themes such as identity and finding home in different contexts and locations, instead of art as a product.

So, what is art therapy?

Art therapy is a method of therapeutic support or counselling. With counselling, we use talking and in creative art therapies we use mediums like drama, storytelling, art, movement and dance as a way of communication and expression of the self and feelings. We use symbols and metaphors, instead of talking we use imagery by working with music, connecting to the body through embodiment and dance. So, it’s kind of a different language that we use. The main core is the same which is having a therapeutic relationship with the person you are supporting. The method I use is based on Jungian psychology, from an analytical psychologist called Carl Jung. The main themes are the collective unconscious, archetypes and bringing the unconscious to the conscious mind to deal with it.

How and when can art therapy be used to heal, especially with the refugee and migrant community?

Art therapy can be categorised as almost non-verbal communication. This is one aspect which I think helps refugees and asylum seekers: there is less talking and less language which is something that newcomers normally struggle with. There is also the understanding of therapy in the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region. For example, the meaning of therapy in Arabic translates more accurately as medical treatment that you need if you are sick, ill and if you are ”crazy”. The word itself when you translate therapy to Arabic is “علاج” which means “treatment”. This is the same word we use for treatment such as cancer treatment or hospital treatment. I feel that art therapy is softer and easier for people to engage with, and they can start to slowly connect, especially if they have never come across it or they have stereotypes. It’s not like BOOM… you have to tell me your life story, tell me what happened to you, this is your trauma. The direct, one-to-one, European style of talking therapy doesn’t work with refugees because it’s a different culture that we are imposing on them.

Art therapy can be useful for anyone who has gone through trauma, not just refugees and asylum seekers. Yet, due to the negative connotations that come with therapy in Eastern cultures, this alternative method can help individuals explore sensitive ideas in a more comfortable and familiar setting. The mainstream method, whereby a therapist typically asks direct questions to their client in a one-to-one setting is not a one-size-fits-all approach. The origin of the concept of therapy was created in rich Western countries, by Western people for Western people. The indirect nature of art therapy, as well as its group setting, makes mental healing and wellbeing accessible to anyone regardless of different cultural norms, such as coming from collectivist cultures wherein community and group identity takes a central role above the individual.

You explore “psychological homelessness” in your practice, can you explain this further?

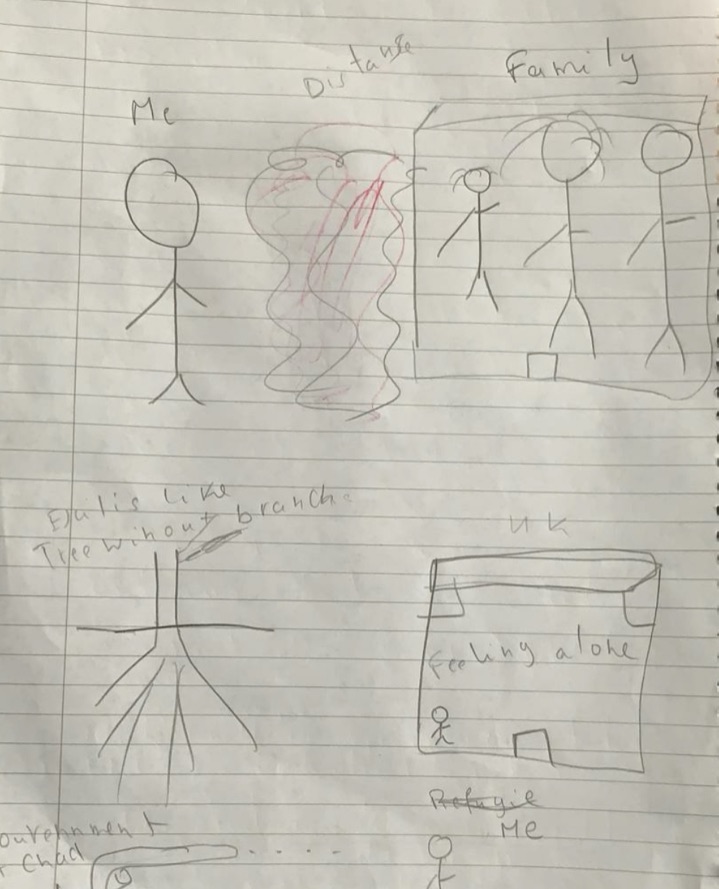

Psychological homelessness is when you are not safe in your own skin. It could be when you lose your identity, maybe when you are abused… when you don’t feel a safe place inside you. It’s drawn from a very old idea called the ‘secure base’. If as a toddler you never had a secure base you don’t know what it is like to feel safe. When you are psychologically homeless you need to find a way to find this internal home before going any further. It’s like you want to build a house but you don’t have any bricks. These bricks have two elements: firstly, the concrete aspect to ensure that an individual’s physiological needs are met – food, drink, shelter, clothing and safety. But also the psychological aspect that can be addressed by going inwards and reconnecting with yourself so you can rebuild yourself again.

What does home mean to you? Is it physical or mental; internal or external?

It’s very difficult, I still can’t say I know what home is yet. I would like to say that I’m moving towards the idea that home is internal, it’s something you find inside you, but it is also a physical entity and it’s something that you have to feel in your body. For me, I think home is the feeling of fire, the warmth, the family… when I feel safe to be who I am. But at the same time it’s when I eat my mum’s food, when I sit at my table, when I bring something from Palestine and have it here in my home in London.

When I ask this question to young refugees or asylum seekers, they say it’s family and they often draw it as symbols of a tree and food. This comes from nurturing which is connected to the Mother archetype. The Mother archetype has a duality which can help us understand the meaning of home. Home can be both good and evil, like the archetypes of the mother and the stepmother/witch. Especially with the stories of refugees and asylum seekers, when your country doesn’t want you, wants to persecute you, what happens to the perception of home, and of safety? The duality of the Mother can flip from positive to negative. Where can you find the positive sense of home again? Can you ever find it? Do you need to create it from scratch? I believe that each one can access this Mother archetype inside of us, so maybe by connecting to that, you can nurture yourself, you can rebuild a positive sense of home again if it’s completely lost.

What role can the arts play in helping to get closer to this feeling of home?

I feel that through art there is a metaphor that can hold you. As a drama therapist, I use stories which have metaphors and elements of home and safety. We use ‘dramatic distancing’: we distance ourselves, embody the feelings, and reflect on it. There is an amazing story called ‘The Boy who Lived with Bears’ which is the first version of Mowgli or Tarzan, where a mother bear takes care of a child who is abandoned. I remember in one session we were acting out the story and a young boy wanted me to be the mother bear, and he wanted me to embrace him and to shelter him with my arms. This embodiment of him taking the role of my son offered him the sense of nurturing and safety. I think art supports you to access this nurturing in an indirect way where people can be drawn to it unconsciously, without judgments. We create rituals and create a sense of community between us. I, as a wounded healer, being a Palestinian raised in Israel, can relate to and understand their cultural complexities. We meet on a common ground where I can guide them on their journeys.

Do you have any final thoughts or messages to share?

I think maybe that home is not something to find, it’s maybe just something to try to find. The way to find home is to lose it, and part of the journey to find your home is to be invited on the journey. When you lose your home, you can’t just find it, you need to have a process to find it. I use The Hero’s Journey, which is a term from Joseph Campbell. Every hero or heroine must lose their home, to have a calling, to go to another place, slay the dragon, they have some mentors on the way and they will return home differently, but they will find home again. So, perhaps when we find ourselves, we will be able to find home.

To be able to achieve the feeling of home again poses a difficult journey, one so complex that the end goal will always be hard to reach. Yet, the ways in which we can build home once again are perhaps within ourselves and are more abstract than we once thought. Art can be used as a way to heal past traumas and explore ideas of ruptured identity and finding home again, as it transcends culture, race, language and background. It does not discriminate. Art therapy is increasingly showing itself as an effective, accessible and culturally competent tool to explore mental health issues and psychological conflict. With growing awareness of its power and increasing support of initiatives like El-Bayet from governing bodies and organisations, the steps to finding home in every individual’s Hero’s Journey will be all the more attainable.

Hear more from Elias and others by supporting independent journalism.